I would like to share some pioneering writing about Kartika by Astri Wright, which was first published in 1999. This is a short excerpt from an informative, insightful and personal article in which Dr Wright discusses three Indonesian, female, modern artists - Kartika Affandi, Lucia Hartini and Murni - and explores her relationship with them as a scholarly writer. Wright’s 1994 book, Soul, Spirit and Mountain: Preoccupations of Contemporary Indonesian Painters (Oxford Univ Press) includes the first sustained discussion of Indonesian women artists, including Kartika, published in English.

Dr Astri Wright is a Professor of Art History specialising in South & Southeast Asian Art and Indonesian Modern Art, at The University of Victoria in Canada. She has known Kartika and maintained a close relationship with her since 1987. I am grateful for Dr Wright's official involvement with the Kartika film documentary as a "Modern Indonesian Art History Consultant" and for the informal encouragement and direction she has generously given to the project and myself personally from the start.

The following is excerpted from:

Self-Taught Against the Grain: Three Artists and a Writer

by Astri Wright

© Astri Wright, text and photos reprinted with the author's permission

[Complete text first published in: Flaudette May Datuin, Ed., Women Imaging Women: Home, Body, Memory. Conference Proceedings. Manila: University of the Philippines Dept of Art Studies, The Ford Foundation Manila, and The Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1999, pp.118-154]

“Høyr de dette, de jentur unge,

No vil me tala med mål og tunge...”

(Whisper:) “Listen closely, all you young girls;

Now I will speak the tale, with both voice and tongue...”:

I will sing to you of Kartika,

woman warrior of Yogyakarta,

on the island of Java.

This is not, my children,

a once-upon-a-time tale:

this is now.

I sing of Kartika, of Yogyakarta,

on the island of Java,

in an archipelago wrongly named

in foreign scripts written with local blood ...

But this tale is not about war and death,

it is about a warrior woman who uses the blood

that washes her flesh

moon blood that feeds the soil

for birthing, not killing,

and for life, not death.

For birthing herself anew

and blazing the way

for others to follow.

Kartika Affandi born in 1934, is the leading radical figure of the first generation of modern women artists in Indonesia.21 Her painting spans a broad range of themes and palettes, from landscapes, portraits of working people, village and urban scenes and self-portraits. Since abandoning oil paints for acrylics in the early 1990s due to the health hazards of long-term exposure to oils and paint thinners, her colours have become even more vibrant and she is freer to move around with her canvases, which suits her technique and lifestyle better.

As an artist, Kartika self-consciously pioneered her own kind of 'difference' in art and life, in turn, fulfilling and departing from the expected roles of modern artists and of women of class or well-known family background.22 Compared to the Euro-American modernist pattern, Kartika’s artistic training was unusual: she never studied art formally or systematically, but learned her approach to painting from her father. Affandi, celebrated eccentric pioneer of modern Indonesian painting, taught her not to try to paint what she saw, but rather aim directly for the expression of what she felt.23 She adopted her father’s techniques of painting directly from the model, in situ, in their own environments, and applying and smearing the paint with her hands and fingers directly onto large, primed canvases. Thus, from the beginning, the artist physically immerses herself in and merges with her artistic medium. By the time she finishes a painting, Kartika would be covered with paint up to her elbows.

Insisting on both the time and right to pursue her art and insisting on maintaining her self-respect in her private life (see Wright 1994b), Kartika experienced the social cost exacted of women who chose to challenge the normative roles of wife and mother. She paid, with social ostracization and sexist reviews, for presuming to become a modern artist and for insisting that the letter of Islamic marriage law should be followed equally for men and for women. While other (male) Indonesian artists, whether in the European art historical tradition or the Indonesian, were not faulted for producing work that stylistically placed them squarely within a particular school or tradition, pioneered and developed by its forerunner(s), Kartika was faulted for painting “too much like her father”. Meanwhile, to stick with the Indonesian context, this charge was never to my knowledge levied at Basuki Abdullah, even though his painting was stylistically, for the first three decades of his career, at least, just like that of his father, Abdullah Suryosubroto. Had the issue been raised, early Indonesian critics might have said: “But his themes and subjects are so different from his father’s!” While such an observation is equally true when we compare Kartika with Affandi, this seems to escape critical notice.

I first met Kartika in 1987, at what was then her father’s museum in Yogyakarta. I was hoping to interview Affandi, the living legend of the first generation of Indonesian-Modernist painters -- self-taught, world-taught, colonialism- and nationalist revolution-taught. Awed at approaching the old, partly deaf man seated in his museum, it was Maryati, his wife, and Kartika his daughter, who nudged me forward and ensured that the young green foreign researcher didn’t turn on her heels and flee. it was only later that I became aware that Kartika and Maryati were both artists in their own right.24 Kartika’s work, particularly her experimental symbolic-expressionist self-portraits, was so different from anything else I saw in Indonesia and so aesthetically honest and powerful, narratively raw and immediate, that I had to engage with it. The fact that I, coming from a Euro-American background, did not have the ingrained Javanese recoil (so dominant in the modern Indonesian art world) at dramatically expressed, self-referential emotion, helped connect us. It was my fortune that she opened her arms to me as a researcher and friend.

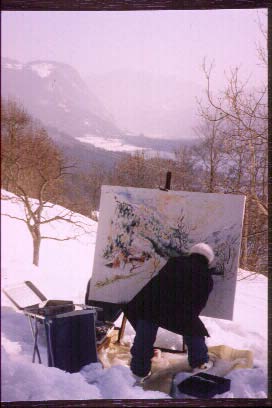

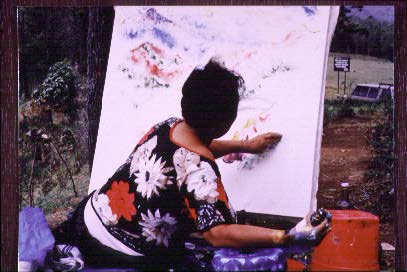

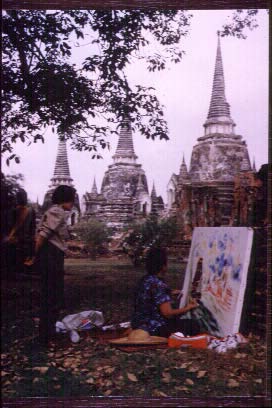

Kartika Affandi is a forerunner for women establishing themselves as modern artists in Indonesia because, through her struggle for visibility, gallery access and critical acceptance in a post-colonial modern art world patterned on the Dutch model, she has become a determined, self-motivated individual with a norm-bending style of her own. Where women of her generation and class did not wear casual clothing in public in the 1980s, she did. Where others did not drive a van around alone, she did. While many would hesitate to study the ax-split head of a buffalo, she didn’t. Another aspect of her behaviour which flies in the face of normative behaviour for her strata of women in Java is travelling alone. She has made many journeys in Indonesia, Asia, Europe and elsewhere, often alone, in order to paint. She has painted, outside, in the freezing snow in Austria and in the burning hot deserts of Australia. She has painted in the small, intimate neighbourhoods of Japanese towns and on the wide, densely populated Piazza di San Marco in Venice. And always, of course, in her own country.

The dynamic of a woman from Java, monetarily poor while growing up but exposed to a nationalist ethic and an internationalist artistic culture, going into the jungles of tribal West Papua (“Irian Jaya”) to paint Asmat men and women, into the Australian desert to paint Aboriginal men and women, or travelling through the countryside in China to paint men and women of Han and other backgrounds, provides fascinating material for a discussion of the process, content, and motivations in such interracial and intercultural interactions. Kartika’s occasional practice of placing herself in the canvas with the racially ‘other’ features of the place adds another dimension to the discussion. While conclusions are open-ended, my analysis, based on her example, concludes that not all imaging of ‘others’ need be exploitative or silencing. Kartika Affandi’s painting, I argue, demonstrates how representing ‘others’ can also be a way of furthering their voices and their presence, within their contexts and beyond.

Driving around together, swimming in her wilderness-hermitage pond, and even travelling to paint, together, chatting in hotel rooms and revolution-era warung25 in Jakarta, we have exchanged, shared, laughed, cried and probed many aspects of life, gender, culture, and art and their connections. Watching how Kartika mustered to me unusual spiritual and emotional resources through one of the hardest times in her life, taught me much about the kinds of choices we have to make and can make, at important junctures in our lives. I also sometimes argue with Kartika. It is always about the same thing: her prospects for a long life. Her bad hip and arthritic bones make it hard for her to walk; perhaps her childhood poverty caused the effects malnutrition does which show up in her mature age, certainly giving birth eight times took its toll. In any case, she does not think she will live to a very old age. She just has this feeling. When Kartika said this to me for the first time in July 1994, ignoring my protestations, it was a statement of fact devoid of melodrama. And then she went on to say: “And only you, Astri, know me and my work well enough to write about me after I am gone.”

I heard this with a mixture of surprise and worry: honored that she would feel this way, I was overwhelmed, not at all sure that I was up to such a task, and believing in a pluralistic discourse, certainly not alone. But the point here is how such a moment illustrates how it can happen that what starts as a research project, with untried-idealist (masculinist) intentions of objectivity and non-personal involvement, can become part of a life-long relationship that functions on many levels, involves many kinds of intelligence (IQ, EQ, and more). The field work relationship can involve an imperceptibly growing responsibility towards the people you work with. (And sometimes their ideas of your ability/role supersedes your own or that which academic conventions would deem acceptable). These are things which must be negotiated openly, both in the field and back in the academic setting, and to be able to be open about such things, a significant degree of familiarity and trust are necessary, in the field, and courage to be seen as a transgressor, in the academic world, as well.

Kartika’s work stands on its own painterly and aesthetic merits. Interpretation is the arena of art writers. While Kartika's visual and verbal narratives do not appear analytical or overtly political, her observations and intent (in her conversation as in her art) go in the same direction as certain feminist writers and activists. In her work, as she scans her heart and the world for subjects to paint, she identifies lacunae of concern, and then she attempts to cross over to that place, becoming a human bridge. This bridge leads to other people who, like her, struggle to be true to themselves. Kartika becomes a listener and sounding board to other experiences while she paints them, in this way sharing empowerment and respect. On the level of discourse analysis, Kartika can be seen to create a marker of this exchange, a signpost (a painting) which has an element of advocacy to it, as it carries the traces of other people's voices further afield.

Kartika provides the world with her own, particularized artistic challenge to the notion of what women are and what women artists should create. She shows us how one woman in Java claimed her freedom to define for herself a place, a style, and a voice of her own, with little societal support once she broke out of the ‘famous daughter’ role. Her example also provided a parallel to the situation of the researcher, going against the grain of her academic advisor, persisting in a field that was considered nonexistent, travelling alone in a culture where women were not supposed to travel alone, carrying out a task not recognized or understood by the majority of people around her. Being embraced by Kartika in the early stages of my research empowered me greatly and still does. This relationship, then, illustrates a different model than that of the researcher with power over the ‘data’ and ‘informants’ who constructs ‘them’ without feedback. There is always power in penning someone else’s story, but Kartika’s and my stories are intertwined and the power shifts from moment to moment, where more often she as the elder (and wiser!) has the lioness’ share, in a relationship where having power is not the goal of either party.

Kartika’s border-crossing provides an argument for how and why a woman of my own ethnic background may still be allowed (and allow myself) to research and write with and about women (and people) of other ethnic backgrounds. Working from a point of departure that takes into account issues raised in Black criticism, avoiding, as far as possible, the monofocus and bias of what bell hooks criticizes as "white men and women ... producing the discourse around Otherness" (hooks, 1990:53) and trying to keep always within sight the importance of ethics in research theory and method, are all part of an ongoing exercise in awareness and reflexivity. Seeing oneself as part co-author, and, like Kartika, as involved with creating signposts designed to carry other people's voices and presences further afield, is one way to minimize dominance and appropriation in cross-cultural work. It is here, in the present era of intensified globalization that Euro-American and Asian women’s concerns intersect. Our concerns meet, not on a platform of historical ‘sameness’, but in the facing of related challenges. In a world where technology, travel and language skills allows for an unprecedented degree of cross-cultural communication, dialogue across differences has a better chance than ever to be fruitful to all parties, even when their conclusions differ.26...

Footnotes:

21. In my analysis, I do not count Emiria Sunassa as the forerunner here, (1) because she does not appear to me to have been particularly radical; (2) because to our knowledge she did not have an ongoing career as an artist, and (3) only one painting by her is known and that is painted from of a wellknown photo taken by Walter Spies of a kecak dance performance in Bali. (This does not preclude that, with more information about Sunassa, this framework could change.) Likewise, according to the framework established in Wright 1994a Chapter 7, I also do not include women who are mainly hobby painters and do not pursue it as their main identity and/or profession.

22. For a longer discussion of Kartika Affandi, with more direct inclusions of her voice, see Wright 1994b.

23. Here, again, I depart from the Indonesian canonization (repeated by Claire Holt and most other scholars, including myself in Wright 1991, 1994) of Raden Bustaman Saleh, the 19th century Javanese aristocratic oil painter, as the father of modern Indonesian painting. While his style, medium and subject-matter indeed was new within the Javanese world,

and as such could be construed as the beginning of a Javanese modernism, outside of Indonesian post-independence revisionist history, there is no evidence of Raden Saleh having held any conception of a larger cultural or political entity beyond Java, any idea like “Indonesia”, or any interest in alternative, radical ideas in Europe of a revolutionary or populist nature which he would have heard of during his decades at European courts. I see Raden Saleh’s contribution to Indonesian art history as an innovation within the realm of Javanese court art and priyayi culture.

24. See Wright 1991, pp. 276-281 for a discussion (not included in my book) of Affandi’s polygamous marriage, from the perspective of Kartika, as well as a discussion of her own experience of her husband’s polygamy.

25. Small, informal restaurant.

26. And yet, all parties in such conversations must remain acutely aware of the challenges inherent in the process. Sophisticated communication across cultural gaps can easily twist and turn into an opposite, unintended dynamic. The moment when one person gains an upper hand and wields it, often without being aware of it. This is often the person from the strongest economy, with the highest formal education, and the habit of proceeding with a sense of personal (and often institutional) authority; in the research situation, this is often the researcher.

Astri Wright Selected Bibliography

Wright, Astri. 2000. “Difference in Diversity: Women as Modern Artists in Indonesia,” in Laura Summers and Bill Wilder, Eds. Gendered States; Modern Powers: perspectives from Southeast Asia. England: Macmillan Press, St. Martin’s Press. See: <http://www.javafred.com>

_____. 2000 "Lucia Hartini, Javanese Painter: Against the Grain, Towards Herself." in Nora Taylor, Ed., Studies in Southeast Asian Art: Festschrift for Prof.Stanley J. O'Connor. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ.South East Asia Program Publications, pp. 93-121.

_____. 1999. “Thoughts From the Crest of a Breaking Wave.” in Timothy Lindsey and Hugh O’Neil, Eds. AWAS! Art from Contemporary Indonesia. Melbourne: Indonesian Art Society, pp.49-69 The text can be found at: <http://www.javafred.com> under READING.

_____. 1998. "Resistance in the Visual Field: Activist Artists in Indonesia in the 1990s," in Ing-Britt Trankell and Laura Summers, Eds, Facets of Power and Its Limitations: Political Culture in Southeast Asia. Uppsala: University of Uppsala Studies in Anthropology 24, pp. 115-146.

_____. 1995. "The Seniwati Gallery for Women Artists in Bali." Art and Asia Pacific, Vol. 2, No. 2 April 1995), pp. 32-35. NOTE: This essay was republished in Asian Women Artists, Roseville, NSW/Singapore: Fine Arts Press and IPD, 1995.

_____. 1994a. Soul, Spirit and Mountain: Preoccupations of Contemporary Indonesian Painters, Kuala Lumpur-Oxford-New York: Oxford University Press.

_____. 1994b. "Undermining the Order of the Javanese Universe: Kartika Affandi-Köberl's Self-Portraits," Art and Asia Pacific, Vol. 1, No. 3 (June 1994), pp. 62-72.

_____. 1994c. "The Emerging Herstory of Modern Art in Bali: The Seniwati Gallery for Women Artists." Paper presented at "Southeast Asia and the New Economic Order", the Sixth Annual Conference of the Northwest Regional Consortium for Southeast Asian Studies (NWRCSEAS), University of Washington, Seattle, November 4-6, 1994.

_____. 1994d. "Imagine a World without Men where All the Elements and Space Itself are Yours: Lucia Hartini, a Javanese Surrealist painter." Paper presented at Association for Asian Studies Annual Meeting in Boston, 24-27 March, 1994.

_____. 1991. Soul, Spirit and Mountain: Preoccupations of Contemporary Indonesian Painters. PhD Dissertation. Cornell University Press. (UMI 1992)

The photos reproduced on this page accompanied the original publication. The caption for the three photos below is: "Kartika painting in Austria, Indonesia, Thailand, early 1980s to mid 1990s"