In 1978 I read a collection of art historian Kenneth Clarke’s 1950s lectures, and the one on “The Naked and the Nude” left a lasting impression on me. As I recall, he delineates the two concepts in terms of whether or not they were voluntary: someone in extreme poverty or forcibly stripped of their garments is ‘naked,’ while ‘nude’ describes a person who chooses to be in a state of undress.

Kartika is not shy about nudity or nakedness in her work, though her depiction of the ‘naked’ is about revealing a kind of forced psychological or spiritual exposure rather than someone bereft of clothing, and her ‘nudes’ never try to convey – at least in my view – the body as a mere aesthetic object, but more as a natural part of life that the artist and the subject collaboratively celebrate.

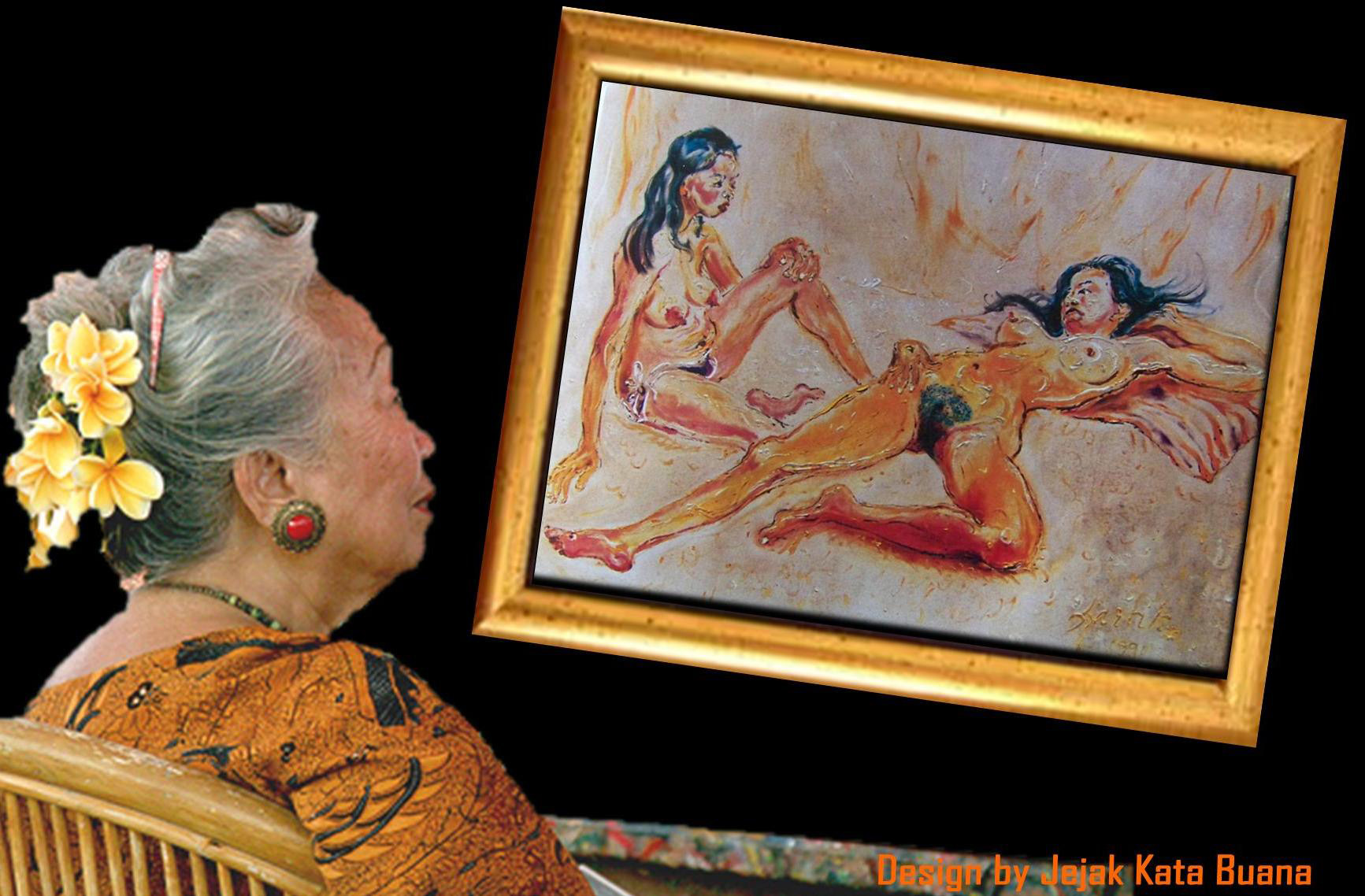

The nude portraits of Kartika pictured here are by the painter Dyan Anggaini, a talented and important figure in the Yogyakarta arts scene, and they have never been exhibited. The Indonesian attitude to nudity and nakedness is complex and varied. On the one hand, I have seen mentally ill persons walking crowded city streets completely naked, seemingly invisible to passers-by, and as recently as 25 years ago it was not unusual to see nude Balinese bathing al fresco in rivers and irrigation streams (though it was impolite to look).

On the other hand, Indonesian public standards of acceptable body-exposure in dress, at the beach, and in art and other media, are far more conservative than in, for example, European or English-speaking countries, and this conservatism seems to be growing. The increasing influence of the cultural ideals of Middle Eastern Islam in this predominantly Muslim country plays a big factor in this, certainly, but so does the increasingly pervasive presence of postmodern advertising and global media, with its depiction of the ‘’beautiful” body as an unattainable and taboo object of desire, a titillating commodity used to hawk products.

Kartika told me that Dyan asked to paint her nude portrait after an experience they shared. They were at a conference of female Indonesian artists in Bali, all living together in a dormitory, and spirits were high. Kartika came out of the bath and entered the dorm room wrapped in a towel, and asked who would like to go see a striptease. Everyone found the idea hilarious, but protested that there were no striptease clups in Bali. So Kartika opened the towel and did a little dance to unanimous applause and laughter.

For the normally demure Indonesian wives and mothers in the dorm this was an outrageous and empowering moment - seeing this great-grandmother laughing and unselfconsciously displaying herself - and Dyan was inspired to paint two nude portraits of Kartika. In the portrait in which Kartika is seated, Dyan makes a visual reference in the background of the picture to a painting of Kartika’s in which she showed her father Affandi as a bright spirit among the sunflowers (itself a reference to a wonderful painting of Affandi’s in which he shows sunflowers in various stages of blossom and decay).

Kartika says she inherited her attitude about the body from her parents who were unfailingly open with her when she was growing up. Her mother Maryati was her father’s nude model, and they never hid this fact from Kartika. And when Kartika had her first child Helfi, Affandi painted himself nude holding his new grandchild, saying he thought it would be odd if he were depicted clothed in the painting when the baby was not.

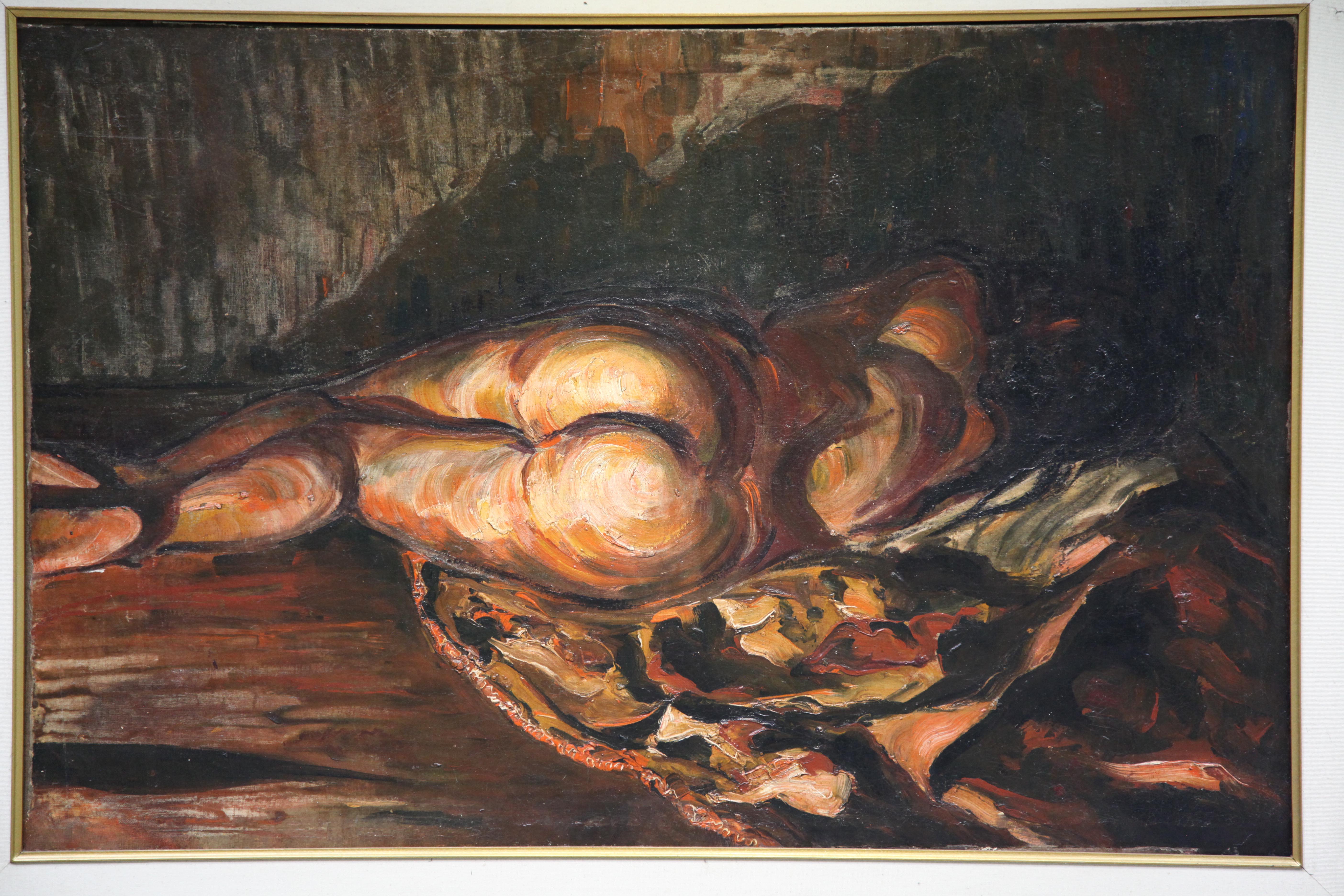

One of Kartika’s paintings shows two nude females, with the genitalia of the reclining figure prominently exposed. When I first saw this painting displayed in her gallery in 2010, she was surprised when I asked her if the figures were her daughters, and she asked why I imagined that. I explained that the depiction seemed compassionate to me, motherly rather than sexy or clinical. Returning to the gallery in 2015 the painting was no longer displayed, so I asked Kartika if she had sold it. She explained that some visitors had complained about it, so she put it away in storage for a while. (I did not want to bother her to get it out that day, so I'll use the photomontage here which is credited to its creator - I'll get footage of the painting later.)

Kartika’s artistic vision can sometimes be powerful medicine for the staid, 21st century, art-consuming public. She had the idea of doing an exhibition of her work which viewers would enter by walking through a sculpture of a monumental vagina, which she conceived as symbolizing entering the artist’s inner world, and then, after experiencing the exhibition, they would exit the vagina sculpture in a kind of “rebirth.” But this idea met with little encouragement or approval – what would the neighbours think? – so she compromised by turning the piece on its side and it became a massive mouth. Kartika told me she didn’t really know if a mouth was necessarily any more or less suggestive than a vagina, but it seemed to placate everybody, so she went along with it.

And then there are her totemic, sculptural representations of the penis, depicting the organ with a face and in various moods: as triumphant, exhausted, lonely, and so on. The statue showing two penis’s encoiled in a snakelike, loving embrace has been the object of the most outrage. She has never exhibited these works outside of her own private gallery.

Kartika’s ‘naked’ art is her most confronting and painful work. In a self-portrait dating from a period when she felt overwhelmed by the pressures of being a dutiful daughter, mother and wife, her brain is exposed as her head is torn apart by pitiless, disembodied hands. In a painting celebrating her ‘re-birth’ after overcoming the trauma of a second failed marriage, she emerges naked in a cloud of blood from her own womb as a wizened and startled newborn. When she realised that her legs were failing her in old age she says she feared that she was already half-dead, and she sculpted a bust depicting herself with half of her skull exposed.

In one of her most moving portraits of Affandi she created an almost overwhelmingly powerful image in which her father is both “nude’’ and “naked.” As Kartika recounts it, although he was overcome by illness and altzheimer’s disease and nearing death, Affandi was still determined to paint, but he lacked the strength to squeeze the pain tubes. He became frustrated and distraught, and in his heated confusion decided to remove his clothes. Kartika portrayed him in this state: as nude and innocent as an infant, yet simultaneously bereft and stripped naked by his infirmity, struggling to bare his soul through his art one last time, as his frail, exposed body is contorted in a final ‘dance of death.’ It is the naked emotion conveyed through the painting, more than the exposed genitalia of her dying father, that makes the work so shocking and painfully honest.